by V. Sundaram

I have already written about the gripping drama relating to the episodes and events that led to the First War of Indian Independence in 1857.

Indian Soldiers Being Executed by British Canons in 1858.

As

I had mentioned, right from the beginning the British Government gave

it the colonial name of ‘mutiny’. When the ‘Indian mutiny’ began at

Meerut Cantonment on the 10th of May 1857, it was given very little

attention in the ‘respectable’ press in England. It took nearly six

weeks for the news to reach London. India was such a ‘non-topic’ and the

‘mutiny’ such a ‘non-issue’ in the British press at that time that the

Times’s initial reporting of the mutiny was actually a response to a

suggestion in the French press that India was revolting against British

rule.

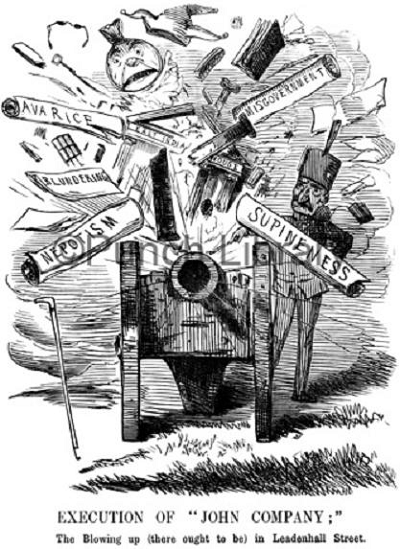

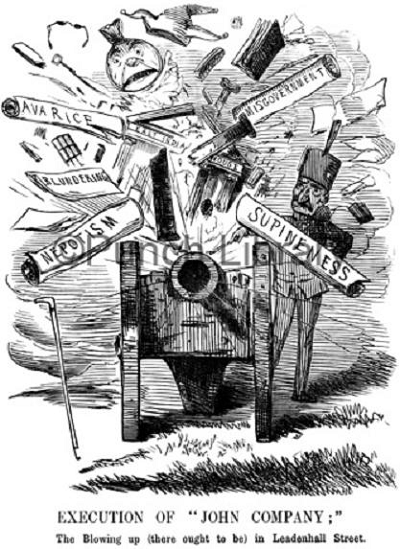

At first there was little coverage of the ‘mutiny’ in the British press. In fact, Punch’s early reporting used the ‘mutiny’ as a way of taking shots at national politics and politicians. A Punch cartoon of 15 August 1857 entitled ‘Execution of John Company: or the Blowing up (there ought to be) in Leadenhall Street’ was critical of the mismanagement of Indian affairs by the East India Company.

The Punch

in the above historic Cartoon had referred to the grave ills that were

affecting the East India Company in India at that time, in 1857 —

avarice, nepotism, supineness and misgovernment.

The Punch

in the above historic Cartoon had referred to the grave ills that were

affecting the East India Company in India at that time, in 1857 —

avarice, nepotism, supineness and misgovernment.

Many of the early reports played up the racial superiority of the British race. For example the Saturday Review wrote about the ‘resolute vigour of the Anglo Saxon race’. Despite these general aberrations, the British Press remained fairly dispassionate until after the massacre at Cawnpore on 15 July 1857. By 22 August, Punch was running a full page cartoon, ‘The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger’. This cartoon has been reproduced below.

Punch was known for its dispassionate cynicism. Even Punch

lost its balance when in August 1857 it published the above cartoon

depicting the British Lion attacking a Bengal Tiger that had attacked an

English woman and child. This cartoon received considerable attention

at that time, with the New York Times writing a piece about it in

September 1857 ‘as emblematic of a near-universal British desire for

revenge’. It was re-issued as a print, and made the career of John

Tenniel who later became very famous as the illustrator of Alice in Wonderland.

Punch was known for its dispassionate cynicism. Even Punch

lost its balance when in August 1857 it published the above cartoon

depicting the British Lion attacking a Bengal Tiger that had attacked an

English woman and child. This cartoon received considerable attention

at that time, with the New York Times writing a piece about it in

September 1857 ‘as emblematic of a near-universal British desire for

revenge’. It was re-issued as a print, and made the career of John

Tenniel who later became very famous as the illustrator of Alice in Wonderland.

From October 1857 onwards, many full page cartoons in Punch focussed on Britain’s duties in India while some of the articles and poems sensationalized the events. The shocking descriptions of brutal murders in Cawnpore must have recalled in the British mind images of the Black Hole of Calcutta about a century before, and rekindled memories of earlier sepoy mutinies in India of 1764, 1806, 1824.

The

whole of England was shocked by the barrage of press reports about

atrocities carried out on Europeans and Christians by the Mutineers in

India. Consequently, the scale and savagery of the inhuman punishments

handed out by the British “Army of Retribution” in India were considered

generally appropriate and justified by the public of England at that

time. The September 1857 issue of Punch carried a print titled Justice by Sir John Tenniel. This print can be seen below.

The

whole of England was shocked by the barrage of press reports about

atrocities carried out on Europeans and Christians by the Mutineers in

India. Consequently, the scale and savagery of the inhuman punishments

handed out by the British “Army of Retribution” in India were considered

generally appropriate and justified by the public of England at that

time. The September 1857 issue of Punch carried a print titled Justice by Sir John Tenniel. This print can be seen below.

Martin Tupper was a popular poet of the time who brought out the atrocities of the ‘mutiny’ in a graphic manner through his fiery poems. A contemporary critic commented ‘More than anyone else, Martin Tupper succeeded in creating a ferment of indignation and thus played a major part in shaping the public’s response’.

His poems, filled with clarion calls for the razing of Delhi and the erection of ‘groves of gibbets’ were telling: Here is a sample of his rousing and roaring British Imperial anti-Indian verse:

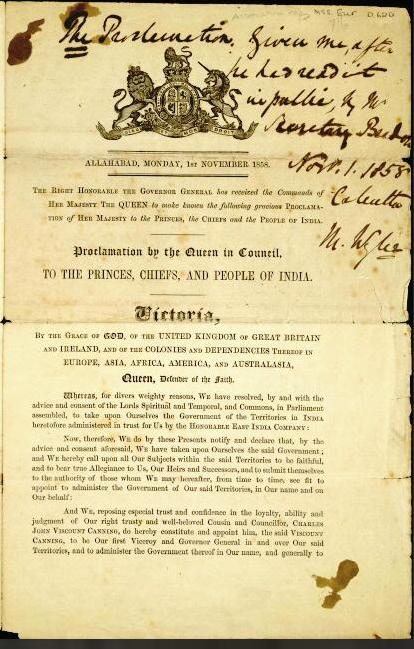

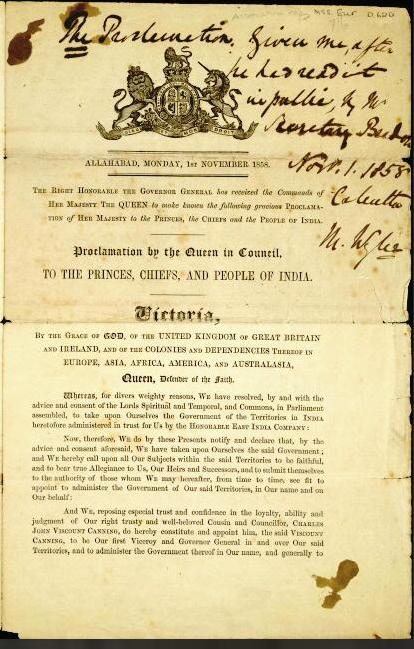

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation in 1858 - Page 1

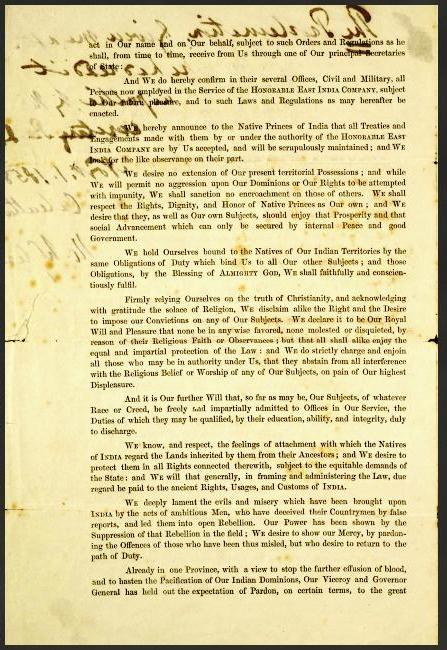

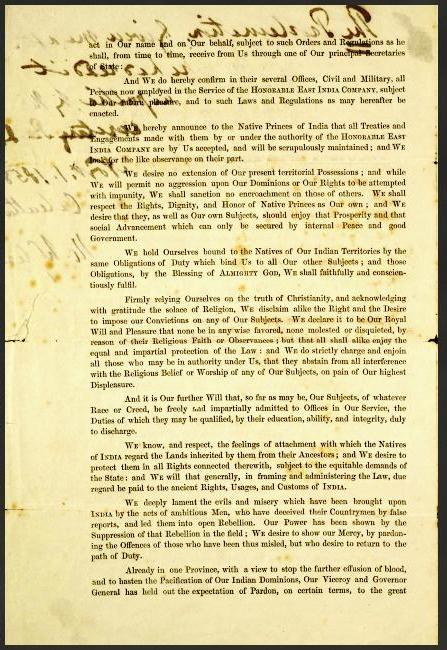

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation in 1858 - Page 2

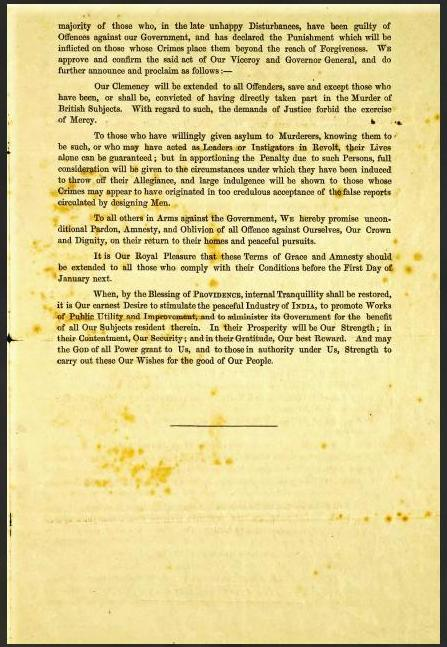

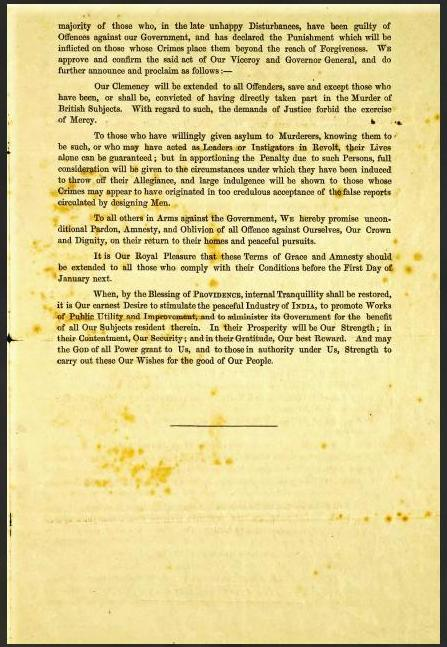

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation in 1858 – Page 3

Source : http://www.boloji.com

I have already written about the gripping drama relating to the episodes and events that led to the First War of Indian Independence in 1857.

Indian Soldiers Being Executed by British Canons in 1858.

At first there was little coverage of the ‘mutiny’ in the British press. In fact, Punch’s early reporting used the ‘mutiny’ as a way of taking shots at national politics and politicians. A Punch cartoon of 15 August 1857 entitled ‘Execution of John Company: or the Blowing up (there ought to be) in Leadenhall Street’ was critical of the mismanagement of Indian affairs by the East India Company.

Many of the early reports played up the racial superiority of the British race. For example the Saturday Review wrote about the ‘resolute vigour of the Anglo Saxon race’. Despite these general aberrations, the British Press remained fairly dispassionate until after the massacre at Cawnpore on 15 July 1857. By 22 August, Punch was running a full page cartoon, ‘The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger’. This cartoon has been reproduced below.

From October 1857 onwards, many full page cartoons in Punch focussed on Britain’s duties in India while some of the articles and poems sensationalized the events. The shocking descriptions of brutal murders in Cawnpore must have recalled in the British mind images of the Black Hole of Calcutta about a century before, and rekindled memories of earlier sepoy mutinies in India of 1764, 1806, 1824.

The

whole of England was shocked by the barrage of press reports about

atrocities carried out on Europeans and Christians by the Mutineers in

India. Consequently, the scale and savagery of the inhuman punishments

handed out by the British “Army of Retribution” in India were considered

generally appropriate and justified by the public of England at that

time. The September 1857 issue of Punch carried a print titled Justice by Sir John Tenniel. This print can be seen below.

The

whole of England was shocked by the barrage of press reports about

atrocities carried out on Europeans and Christians by the Mutineers in

India. Consequently, the scale and savagery of the inhuman punishments

handed out by the British “Army of Retribution” in India were considered

generally appropriate and justified by the public of England at that

time. The September 1857 issue of Punch carried a print titled Justice by Sir John Tenniel. This print can be seen below.Martin Tupper was a popular poet of the time who brought out the atrocities of the ‘mutiny’ in a graphic manner through his fiery poems. A contemporary critic commented ‘More than anyone else, Martin Tupper succeeded in creating a ferment of indignation and thus played a major part in shaping the public’s response’.

His poems, filled with clarion calls for the razing of Delhi and the erection of ‘groves of gibbets’ were telling: Here is a sample of his rousing and roaring British Imperial anti-Indian verse:

And England, now avenge their wrongs by vengeance deep and dire,

Cut out their canker with the sword, and burn it out with fire,

Destroy those traitor regions, hang every pariah hound,

And hunt them down to death, in all hills and cities ‘round.’

Albumen silver print by Felice Beato, 1858 The hanging of two participants in the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The December 1857 issue of Charles Dickens’ Household Words contained an essay by Dickens on the Indian mutiny in which he spoke like a savage colonial tyrant. Let us hear his imperious words: ‘I wish I were a Commander In Chief in India. The first thing I would do to strike that Oriental Race with amazement....should be to proclaim to them that my holding that appointment by the leave of God, to mean that I should do my utmost to exterminate the race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested; and that I was there for that purpose and no other, . . . now proceeding, with all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the Earth.’

The distinguished Victorian scholar Peter Brantlinger has written that no event raised national hysteria in Britain to a higher pitch, and no event in the 19th century took a greater hold on the British imagination than the Indian mutiny. To quote his exact words ‘Victorian writing about the mutiny expresses in concentrated form the racist ideology that Edward Said calls Orientalism’.

Speaking in the House of Commons in July 1857, Benjamin Disraeli described the uprising of 1857 as a ‘national revolt’ while Lord Palmerston, the then Prime Minister, tried to down play the scope and the significance of the event as a ‘mere military mutiny’. Reflecting this debate, the early historian of the rebellion, Charles Ball, though he sided with the name of ‘mutiny’ in his title (using mutiny and sepoy insurrection), yet he labeled it a ‘struggle for liberty and independence as a people’ in the text of his book.

The 1857 rebellion saw the end of the British East India Company’s rule in India. In August 1858, by the Government of India Act 1858, the company was formally dissolved and its ruling powers over India were transferred to the British Crown. A new British Government Department, the India Office, was created to handle the governance of India, and its head, the Secretary of State for India, was entrusted with formulating Indian policy. The Governor-General of India gained a new title as Viceroy of India and he was entrusted with the responsibility for the implementation of the policies devised by the India Office in London.

The December 1857 issue of Charles Dickens’ Household Words contained an essay by Dickens on the Indian mutiny in which he spoke like a savage colonial tyrant. Let us hear his imperious words: ‘I wish I were a Commander In Chief in India. The first thing I would do to strike that Oriental Race with amazement....should be to proclaim to them that my holding that appointment by the leave of God, to mean that I should do my utmost to exterminate the race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested; and that I was there for that purpose and no other, . . . now proceeding, with all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the Earth.’

The distinguished Victorian scholar Peter Brantlinger has written that no event raised national hysteria in Britain to a higher pitch, and no event in the 19th century took a greater hold on the British imagination than the Indian mutiny. To quote his exact words ‘Victorian writing about the mutiny expresses in concentrated form the racist ideology that Edward Said calls Orientalism’.

Speaking in the House of Commons in July 1857, Benjamin Disraeli described the uprising of 1857 as a ‘national revolt’ while Lord Palmerston, the then Prime Minister, tried to down play the scope and the significance of the event as a ‘mere military mutiny’. Reflecting this debate, the early historian of the rebellion, Charles Ball, though he sided with the name of ‘mutiny’ in his title (using mutiny and sepoy insurrection), yet he labeled it a ‘struggle for liberty and independence as a people’ in the text of his book.

The 1857 rebellion saw the end of the British East India Company’s rule in India. In August 1858, by the Government of India Act 1858, the company was formally dissolved and its ruling powers over India were transferred to the British Crown. A new British Government Department, the India Office, was created to handle the governance of India, and its head, the Secretary of State for India, was entrusted with formulating Indian policy. The Governor-General of India gained a new title as Viceroy of India and he was entrusted with the responsibility for the implementation of the policies devised by the India Office in London.

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation in 1858 - Page 1

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation in 1858 - Page 2

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation in 1858 – Page 3

On

November 1, 1858, Queen Victoria issued her famous proclamation and

this proclamation was read out in public by duly designated authorities

in all the district and taluk headquarters of British India on that day

and later almost daily till the end of December 1858.

I am giving below the most important excerpt from Queen Victoria’s proclamation of 1st november 1858:

I am giving below the most important excerpt from Queen Victoria’s proclamation of 1st november 1858:

‘We

know, and respect, the feelings of attachment with which the natives of

India regard the lands inherited by them from their ancestors, and we

desire to protect them in all rights connected therewith, subject to the

equitable demands of the State; and we will that generally, in framing

and administering the law, due regard be paid to the ancient rights,

usages, and customs of India.’

Post Script:

I am presenting below some pictures / illustrations / paintings relating to the First War of Indian Independence in 1857.

Early

British atrocity. Blowing away rebellious sepoys after tying them to

cannons (May 21, 1857). From Sir Colin Campbell, 'Narrative of the Indian Revolt from its Outbreak to the Capture of Lucknow', London, 1858.

Depiction of 'Native' barbarism against the colonialists. Images such as these - of British martyrdom at the hands of brutish 'natives' who did not spare even women and children - deeply influenced public opinion in England.

Repulse of a sortie. By G.F. Atkinson. (Reproduction of water colour.)

Colonel Platt killed by mutineers at Mhow.

(Charles Ball, 'History of Indian mutiny', Vol. I.)

Depiction of 'Native' barbarism against the colonialists. Images such as these - of British martyrdom at the hands of brutish 'natives' who did not spare even women and children - deeply influenced public opinion in England.

Repulse of a sortie. By G.F. Atkinson. (Reproduction of water colour.)

Colonel Platt killed by mutineers at Mhow.

(Charles Ball, 'History of Indian mutiny', Vol. I.)

I am often enthralled by the mystery of time,

by the mutability of all things, by the succession of the endless ages

and countless generations. When I look back on the stirring times and

hair rising episodes of the First War of Indian Independence, I cannot

help quoting the immortal words of Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) in his

classical work ‘French Revolution’:

“The

Fireship is Old France, the old French Form of Life: her crew a

generation of men. Wild are their cries and their ragings there, like

spirits tormented in that flame. But on the whole are they not gone, Oh

Reader! Their Fireship and they frightening the world, have sailed away;

its flames and thunders quite away, into the Deep of Time. One thing

therefore History will do: Pity them all: For it went hard with them

all. We, I think can appreciate that figure, sailing away as we are on

our own burning fireship, into the Deep of Time … The Mysterious River

of Existence rushes on; a new Billow thereof has arrived, and lashes

wildly as ever round old embankments; but the former Billow with its

loud, and eddyings, where is it? Where?” Source : http://www.boloji.com

Organic fruits and vegetables, animal protein from free-range chicken and eggs, wild-caught diet fish and

ReplyDeletegame meat. A large fire was made in a depression in the sand,

and stones and shells were heated.

Feel free to visit my web blog - http://en.netlog.com